|

BELGIAN FASHION DESIGN

|

LANGUAGE ( r e - a p p e a r a n c e ) |

||||||||||||||||||

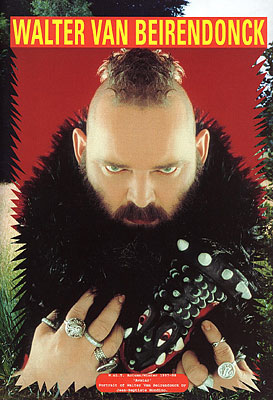

| WALTER VAN BEIRENDONCK: "At one time what you saw on the street was much more interesting. Today I find what you see on the street completely uninteresting, apart from the occasional exception. There was a time when you could actually see a statement by Comme des Garçons on the street a year later, even if it was in a copy produced by some other large manufacturer. Large manufacturers still copy, but in a totally uninteresting way. You keep on seeing the same clothes over and over again. "These days cross-fertilisation is more likely to happen inside the fashion world itself. At one time it still happened between designers on the one hand and the big companies that decide what is worn on the street on the other." | |||||||||||||||||||

|

Little

Red Riding Hood was an innocent young girl who, expecting to see her grandmother

lying in bed waiting for her, either saw her, or wanted to see her, or was

so fascinated by the experience of seeing a carnivore under the bed clothes,

that she ignored her reasonable doubts about what exactly it was that she

was seeing for rather too long, and consequently was swallowed up by the

wolf. However the wolf committed the classic error of falling asleep, was

cut open and deprived of its catch. Little Red Riding Hood was set free,

alive and well. Despite the unvarnished aggression and violence (wolf mauls

child, hunter rips open wolf), all's well that ends well. Little

Red Riding Hood was an innocent young girl who, expecting to see her grandmother

lying in bed waiting for her, either saw her, or wanted to see her, or was

so fascinated by the experience of seeing a carnivore under the bed clothes,

that she ignored her reasonable doubts about what exactly it was that she

was seeing for rather too long, and consequently was swallowed up by the

wolf. However the wolf committed the classic error of falling asleep, was

cut open and deprived of its catch. Little Red Riding Hood was set free,

alive and well. Despite the unvarnished aggression and violence (wolf mauls

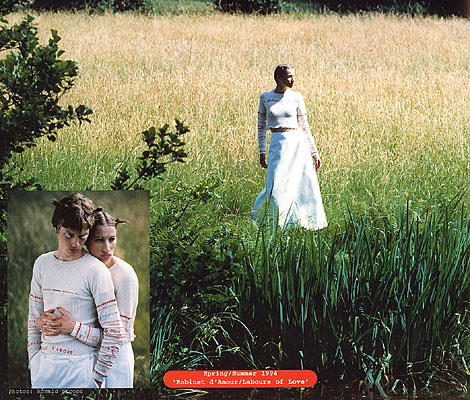

child, hunter rips open wolf), all's well that ends well.We all know this fairy tale. It is rooted in that substrate of stories, legends and myths, which since the beginning of time have helped men to deal with their fears of the unknown, of darkness and of death. They tell of the initiation of innocent but fascinated beings into the abysmal gulf of human passions and desires, into the treachery of greed and pleasure, and are full of rules of thumb about how to survive down here. They are populated by a host of imaginary creatures, ranging from gods to dwarfs, all perfectly familiar to us even if we often seem to be unaware of their significance. This mythology bears witness to a set of 'subjugated knowledges' which have survived in popular culture despite repeated and impressive attempts to manipulate, isolate, discipline and deny them - such as the Inquisition, modern academicism, even psychiatry. Even if the exclusive thinking of post-war modernism has banished all this stuff about princes, elves, Vampirella and Batman to the bottom of the list of mental activities, in reserved areas such as fairy stories, comic strips, pulp fiction, film, pop songs etcetera, the mass of people tend rather to discover their 'condition humaine' there rather than in the grand political and social theories of modernism. In 1976 Michel Foucault referred to an "insurrection of subjugated knowledges," knowledge that he saw as characterised by a concern... with a historical knowledge of struggles. In ... the disqualified, popular knowledge ... lay(s) the memory of hostile encounters which even up to this day have been confined to the margins of knowledge."* This was confirmation of a critical revisionism, a movement which abandoned the 'universal intellectual' and opposed the assumptions of the avant-garde and its institutions. So, to take just one example, around the time of the German artist Anselm Kiefer, the primaeval national myths of Germany, manipulated by Nazism and totally repressed since the Second World War, began to be plastered on monumental canvases. Something along the lines of 'this is the German substrate, never forget it'. In the early eighties western culture saw its criticism reformulated. The dynamism of the avant-garde, the successive attempts at global solutions, each correcting the last, was watered down into a self-congratulatory bickering amidst the ivory towers. The new agenda was concerned with institutional 'power-knowledge', and began a radical questioning of its exclusion mechanisms. 'Many signs of new temperament, as for example Rei Kawakubo's first catwalk show for Comme Les Garçons, indicated that even the institution of fashion could accommodate more than a limited number of dominant lines of beauty and taste. Like many of his generation, Van Beirendonck seems keenly aware of these exclusions. (Anyone who spent part of his youth subject to the 'law and order' of a boarding school would certainly be sufficiently confronted with them, even if only in a rudimentary form.) Whereas at this juncture Martin Margiela opted for an 'archaeological' movement which would once more question and deconstruct the assumptions of fashion analytically, Van Beirendonck sought confrontation. In other words, his criticism was based not on a detailed examination of the question but on a confrontation of the question with a barrage of other, 'subjugated' questions. He introduced marginal, 'rejected', codes in dress, such as SM attributes or science fiction suits. His next answer was a radical reintroduction of mythology. As a fully-fledged 'mythographer', he called up images and stories from our collective memory and then short-circuited them with elements from contemporary techno- and cyberculture. The fact that they all join together seamlessly seems to prove that attitudes to highly contemporary technology, such as the Internet, and to the things that happened in ancient myths are not too far removed from one another. Where once the gods threatened us with a deluge, today we face a hole in the ozone layer. Luc Derycke  |

||||||||||||||||||