| SKIN TIGHT

|

|

|

||

|

|

|||

|

||||

| Seeking to define fashion, critics have examined it from various perspectives, including the history of fashion, gender studies, sociology, psychoanalysis, economics, cultural studies, and design. Fashion can signal a cultural climate or contribute to the definition of a culture; it can project the dreams, fan-tasies, and desires of consumer society. Idiosyncratic in nature, fashion personifies individuals-it allows us to transform ourselves at will. Because of its mass appeal, fashion has taken center stage in various museum exhibitions, most notably in Europe and Japan, and increasingly in the United States. Such exhibitions serve as documents for a genre that is of ten transient. Skin Tight: The Sensibility ofthe Flesh investigates fashion as part of visual culture, reflecting increasingly blurred boundaries between fashion and art. The proliferation of fashion images in publications such as Purple, Tank, self service, i-D, Visionaire, Dazed and Confused, and Dutch Magazine suggest that today, designers are seen as cultural producers equal to their counterparts in the various fields ofmusic, performance, film and video, and art. But the marriage between fashion and art is not new. In the early twentieth century, many artists used clothing to contribute to their own mythology and artistic practice and as social commentary. Artists such as Marcel Duchamp, Joseph Beuys, Andy Warhol, James Lee Byars, and Jeff Koons defined themselves, respectively, through the image and associ-ated clothing of the dandy, blue-collar worker, socialite, shaman, and yuppie. Contemporary artists such as Cindy Sherman, Tracy Emin, Philip-Lorca di Corcia, and Wolfgang Tillmans, among others, have produced work for fashion designers' campaigns. Conversely, designers increasingly draw from the daily fabric of our society. The designers featured in Skin Tight-BOUDICCA, Hussein Chalayan, Maison Martin Margiela, Raf Simons, Under Cover, Viktor & Rolf, Walter Van Beirendonck, Bernhard Wil!helm, and A. F. Vandevorst- break from the traditional mode offashion. Li Edelkoort, the only non-fashion designer in the exhibition, forecasts trends in fashion, industrial design, and consumer products. These participants not only transform codes of dress through the construction (and deconstruction) of clothes but draw on influences as varied as architecture, craft, film, art, philosophy, and performance, among others. Skin Tight was conceived around three major categories-the architecture ofthe body, the sexualized body, and the deconstruction ofthe body-that reflect contemporary anxieties and suppositions related both to the body itself and the emotional resonances connected to it. The participants in the exhibition explore the body both adorned and unadorned; the role of mas-querade and fantasy role-play; the need to reveal and conceal one's body; the beauty and imperfections ofthe body concealed; the tawdry and perverse; and the mundane.2 Although Skin Tight is not divided by the three main topics, each participant fits into at least one ofthem. This essay wil! focus on the work ofthree designers whose work exemplifies these categories. |

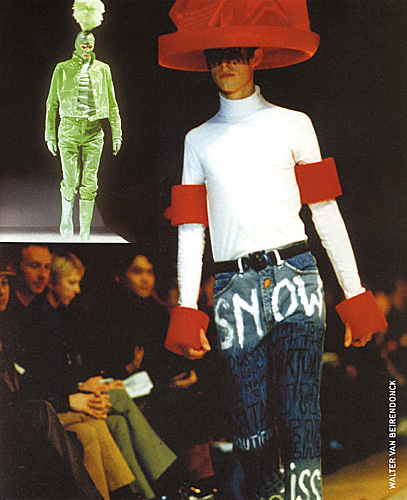

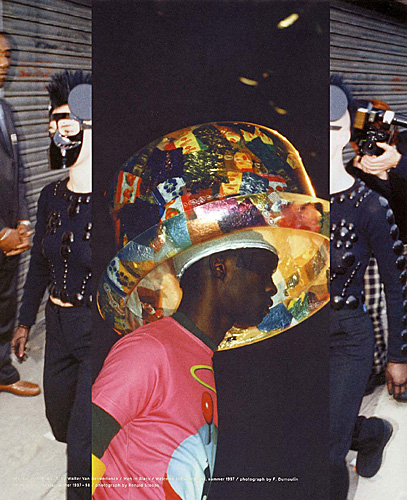

||||

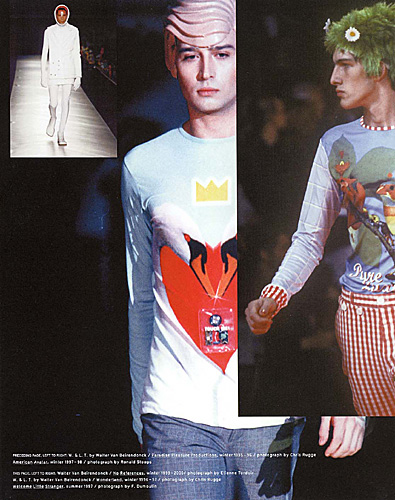

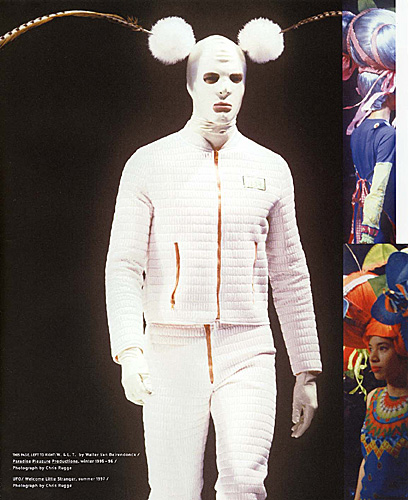

| Hussein Chalayan, a quintessential conceptual designer, addresses, in the words of one critic, "the spatial connotations of the body and how we cultur-ally define ourselves in what we wear and how we act.'" He addresses such topics as geography, religion, ethnicity, and our perception of time and space. For his graduation thesis show in 1993 at Central Saint Martins College of Art and Design in London, Chalayan buried his silk and cotton collection in the ground along with iron fillings, uncovering it several weeks later. The rusty clothes that emerged evoked a sense ofhistory and decay; the passage of time became the central element in the collection. Chalayan's fascination with the body's natural capacity for speed and the way it can be enhanced by technology culminated in the Airplane Dress for the Echoform collection (autumn-winter 1999-2000). The second in a series offiberglass and resin dresses using technology from the aircraft industry, the Airplane Dress contained a switch controlled by the model that allowed £laps of the dress to move horizontally and vertically. In a memorable runway show, Chalayan investigated what it means to be displaced from one's home country as a result of war. InAfter Words (autumn-winter 2000-01), set on a stage set suggesting a sparse living room, chair covers were stripped to form wearable dresses; the chairs then folded to become suitcases. While a mahogany coffee table telescoped to become a tiered skirt, each piece ofthe living-room tableau was removed until the stage was stripped bare. Although at first glance it may appear that Chalayan's designs are unwearable, his emphasis is always on the idea behind the clothes, the context from which they arrive. Originally part ofthe Antwerp Six, a group ofBelgian designers that gradu-ated from the city's Royal Academy in the 1980s, Walter Van Beirendonck came to the forefront of avant-garde design by using confrontational clothes to experiment with sexual taboos, among other issues. He introduced marginal codes of dress, such S & M or body modifications that questioned beauty. Of ten drawing from the worlds of comics and science fiction, Van Beirendonck questions the dark side of mainstream culture, investigat-ing the violent and aggressive undertones of such subject matter. His autumn-winter collection of 1995-96, Paradise Pleasure Productions, combined these topics with Euro-trash club-culture hedonism. As the run-way show opened, the stage was suddenly populated by dozens of men and women clad entirely in latex with only their eyes and mouths left visible. While the clothing and masks referred to sexual fetishism, this collection also suggested commodity as fetishism: the masks can be seen as an indictment of the cult of modeling and the fashion industry itself.' For the collection Believe (autumn-winter 1998-99) Van Beirendonck was inspired by the French artist Orlan, who uses her face as a canvas, undergoing plastic sur-gery to challenge conventional notions of beauty. Exploring the fields of plastic surgery and prosthetic makeup, Van Beirendonck dressed male and female models in clothing that made them look like they stepped out of a fairy tale. The most startling aspect of their dress was their prosthetic facial parts: horns and vertebrae prominently displayed on their faces. Prom the start, Van Beirendonck has avoided fashion trends and movements, focusing instead on developing his startlingly original work. |

||||

| Another member of the Antwerp Six, Martin Margiela also displays fierce independence. Perhaps more than any other contemporary fashion designer, Margiela is truly iconoclastic, probing the construction and deconstruction of clothes. His obsession with the craft and process of designing and making clothes has led him continually to recycle key garments every season, resolv-ing the old with the new. His first collection show, in the fall of 1988, was held in an old Parisian theater. Guests sat on wooden benches and were served cheap red wine in plastic cups, a trademark practice that continues to this day. Margiela played with new shapes and combined unconventional fabrics like jute, plastic, and transparent weaves,'leaving hems and seams unfin-ished and visible. Margiela's collections reflect his analytical view on clothing as he dissects and reconstructs garments, exposing the interior as exterior. For Margiela, proximity is everything; he prefers that his fabrics and forms be seen up close. He oRen chooses unconventional places to show his coIlec-tions, such as a squatters' site and a Salvation Army building. Eschewing the cult of personality, Margiela prefers to be addressed as a group (Maison Martin Margiela) and has never given a face-to-face interview. Even his clothing label remains blank or simply has a number circled to delineate between the various men's and women's lines. Like Maison Martin Margiela, many of the designers in Skin Tight have used runway shows in ways unique to the fashion industry, using unlikely settings to convey a mood or source of inspiration. Along with this, they view the garments they design not solely by their physical construction, but through the conceptual ideas surrounding each collection. For them, the idea behind the collection exists long af ter the garment. These notions exemplify how the work of the Skin Tight designers fits so weIl in the realm of visual culture. Fashion and art share similar impulses: grappling with aspecific form, attempting to create a new language, breaking with tradition, resolving form with content, working with a set of materials, and contributing to a larger dialogue. The work in Skin Tight cannot be analyzed simply as a functional relationship between the body and the cre-ation of clothes; it should be seen instead as a platform for commenting on contemporary concerns, namely reconsideration of the flesh, the pleasures and pains of forming an identity, and, as Caroline Evans so aptly puts it, our sense of "alienation and loss against the unstable backdrop of rapid social, economic, and technological change at the end of the twentieth century."6 |

||||

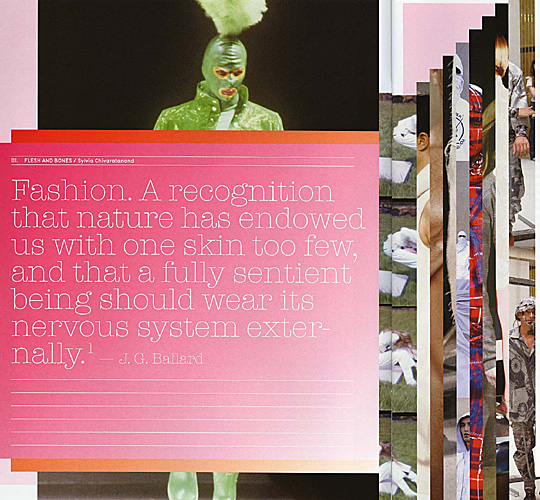

| 1. J. G. Ballard. "Project for a Glossary of the Twentieth Century," in Jonathan Crary and Sanford Kwinter (eds.), Incorporations (New York: Zone Books. 1992), p. 275. 2. See Fiona Anderson. "Museums as Fashion Media." in Stella Bruzzi and Pomelo Church Gibson (eds.), Fashion Cultures: Theories. Explorations end Analysis (New York and London: Routledge), p. 387. 3. Dutch Magazine (January-February 1998). p. 28. 4. 5ee Luc Derycke and Sandra Van de Viere (eds.), Belgion Fashion Design (Bruges. Belgium: Ludion. p.143. 5. Ibid.. p. 290. 6. Caroline Evans. Fashion at the Edge : Spectacle. Modernity and Deathliness (New York and London: Vale University Press, 2003), p4 |

||||

|

||||

It is no coincidence that this exhibition includes fine examples of Belgian fashion. Following in the foot-steps of the Japanese in the early 1980s, Belgian designers gave fashion a new and authentic diarension, a dimension that for more than twenty years has tboroughly altered our vision of fashion aesthetics. When I think of Belgian fashion, I consi.der depth, sensitivity; often modesty, darkness and lightness, identity, and reflection, and never shallowness. But there is no Belgian style as such. Designers such as Walter Van Beirendonck, Bernhard Willhelm, A. F. Vandevorst, Ann Demeulemeester, Dries Van Noten, Martin Margiela, Veronique Branquinho, and Raf Simons are not comparabie, not interchangeable. What binds them is their vision - their talent to give fashion a new content or simpJy a content. It is this dimension that distinguishes them. It is this dimension that lies at the origin of a certain aesthetic sensibility that we gradually started to call "typically Belgian." If you consider tbat avant-garde fashion is a reflection of our times, then Belgian fashion has been reflect-ing, and reacting, in a highly individual way. In the search for its own aesthetics and identity it first went about deconstructing before it could start reconstructing. It analyzed and asked questions so that it could question itself once more. It looked for the soul so that it could start a dialogue with the heart and the intel-lect. It dug in the past so that it could look into the future. It went under the skin. Craftsmanship and vis ion, culture and functionality, gender and aesthetics, concept and sensibility: these are indisputably the tools Belgian designers used to stand out as a generation that has given fashion its own identity, thus proving that fashion is more than it seems. Will this revolutionary way of thinking about fashion change our vision of clothes and beauty? What will be the impact of this vision on our future aesthetic observation ? I wish I could look a few years ahead. Because fashion is constantly moving, like a machine in perpetuaJ motion, every new era will search for new answers. Every artist will continue to question him.self. And every new era will generate new impulses that revolutionary or visionary minds will anticipate by translating them within their own discipline. Serious fashion designers - those who take their profession earnestly - will always react to this context. It is a concept close to the heart of Belgian designers. |

||||

|

||||