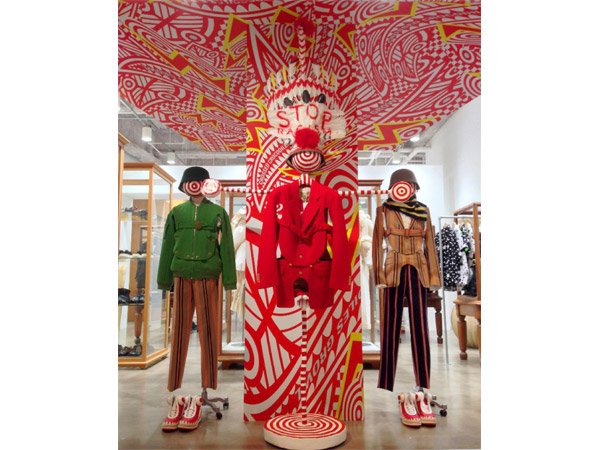

Spend any time in any Dover Street Market in the next few weeks and you�re sure to come across a futuristic totem pole, wrapped in 21st-century tribal gear, topped by a huge feathered headdress bearing the slogan �Stop Racism.� It�s a characteristically provocative signpost for the latest collection from Walter Van Beirendonck, newly installed at DSM under the auspices of Rei Kawakubo herself. The playfulness of the candy-striped totem, the seriousness of the message�it�s a classic WVB combination, and it�s way past time that the world got to see it in its full glory, because until now, Van Beirendonck has been, by and large, a fanboy�s fave. Yet he�s been in business for three decades already. As he says, �It�s not like I�m a young designer starting up,� despite which, there�s an energy, a brashness, an unholy enthusiasm in his work that would put someone half his age to shame. And, best of all, Van Beirendonck is not afraid to make his work say something.

So I got it wrong. The feathered headdresses are inspired by Papua New Guinea, not by Native American Indians.

Yes. But the day after the show, I received a very weird mail from a Native American Indian thanking me for supporting them, referring to everything that had happened with Chanel in Dallas. But I honestly was not aware of that�it wasn�t a reaction to Chanel�s show. I was really inspired by the banners in street protests, but I didn�t want to do actual banners because they would have to be carried. Then, when I was researching, I found these incredible headdresses from Papua New Guinea, which offered an area where we could put a message. So I talked to Stephen [Jones, hatmaker extraordinaire], and he made these pieces on which we sprayed �Stop Racism� in different languages.

It�s such a strong, political collection for you to enter the American market with.

I was selling before in America, but I feel now there is much more interest. People are starting to react to my statements. It�s nice that Dover Street Market is supporting me. It was Rei herself who came to the showroom to buy the collection and talk about an installation. It�s happening in New York, London, and Tokyo.

Interesting that you�ve chosen New York for the headdress with �Stop Racism� in Arabic.

Sometimes these things are happening for a reason. But really, it�s about the headdress height. The tallest one has �Stop Racism� in English, and that�s in Tokyo because it has the tallest space. New York is second tallest. But in the end, I was happy that London has Russian, America has Arabic, and Tokyo has English. It�s by coincidence, but it worked out well.

Indigital Images |

No such thing as coincidence�but I know that it rankled you that America never got you. Is this vindication for you? What do you think changed?

There is now a feeling of respect from press and buyers, which was not there before. It�s been really obvious over the last five or six seasons. One way or another, they really discovered what I was doing, and maybe one way or another I became a little less loud, more mature, with the decision to go in a more structured way, with more worked-out pieces. I don�t feel my way of working really changed. But I think the fashion world changed a bit. I feel that customers are really searching for a �surprise� product, they�re really trying to find excitement.

Most of the time, greater acceptance comes from greater accessibility, but I don�t think it�s like that at all with you. The last couple of collections are just as confrontational as anything you�ve ever done.

What I find out from getting older is that I can do things better. The challenge to do certain things, certain experiments, now comes easier. That�s a nice feeling.

Do you also think that now the customer appreciates something with emotional content, political content? In your new collection, for instance, I didn�t know that �crossed crocodiles� are an African emblem for unity in diversity, and that message couldn�t be more necessary�and more under threat�than right now.

That�s this excitement I�m talking about. The emotion in these garments is what people are looking for. I feel it�s an incredibly tense moment in the world. The military helmets in the collection were a little bit of a prediction of what we�re going through. That�s why I�m so happy that the DSM installation is really showing the helmets, as well as the feathers, alongside the clothes. Because, aside from a little bit in magazines, that message is gone when the show ends. So I�m happy that the whole collection is available in the shops.

Courtesy Photo |

Let�s talk about those helmets. They were candy-colored�

Pink and yellow and light blue. Stephen made them in felt, and he put a little bow on the chin. I think it was inspired by Audrey Hepburn.

That goes beyond irony into satire.

In my fantasy world, I see this as soldiers fighting for a kind of freedom. The helmets are not really referring to an army. It�s more about a freedom warrior, people demonstrating in the street. I always loved the idea of people standing up for diversity, for their right to be different. All the small details, the small messages�it�s nice to work on a collection like this. Of course that bow isn�t necessary, but in my world, it�s important to have that small touch which gives a totally different twist at a certain moment.

And twisting is what you do best. You take the most male emblems�a tailored suit, a soldier�s helmet�and deconstruct or subvert them. Is the idea of subverting masculinity something that�s quite precious to you?

I really enjoy that. It�s a bit like my gender experiments. If you overview all my collections, there�s always been this ambiguity, this masculine irony. For me, it�s interesting to try to figure out how far I can go, what I can push forward. Men�s fashion needs that kind of push.

|